With a nor’easter battering the east coast followed by a brutal cold snap, getting to and around the American Society of Church History/American Historical Association meetings in Washington, D.C., last month was no easy task. For colleagues unable to attend the conference, here’s my response to the insightful reflections on Darkness Falls on the Land of Light presented by Jon Butler, Heather Kopelson, Jon Sensbach, Adrian Weimer, and Molly Worthen (with special thanks to Laurie Maffly-Kipp for stepping in to read Molly’s paper).

It’s so great to be here this afternoon. I’m thrilled and honored to have an opportunity to talk about Darkness Falls on the Land of Light. I’d especially like to thank T. J. for putting this roundtable together, to the American Society of Church History for sponsoring this event, and, especially, to Jon Butler, Heather Kopelson, Jon Sensbach, Adrian Weimer, and Molly Worthen for taking time out of their busy academic schedules to read and reflect on my book.

Where do we go from here? Jon Butler’s question is an important one, and well worth considering as a group this afternoon.

And I should probably start by acknowledging, somewhat sheepishly, that Darkness Falls, as Jon Sensbach has suggested, is a resolutely local study. Or, as I like to think of it: it’s a charmingly old school, throwback book. Many of my models and interpretive frameworks derive from the New Social History scholarship of the 1970s. I’ve tried not to argue beyond the local. This is not a book about the New England origins of the evangelical self. But it’s nonetheless a regional study of a people who, I believe, led spatially circumscribed religious lives.

And yet it’s equally clear from the panels and papers at this conference that scholarly interests have moved on in recent decades. Atlantic world, transatlantic, global histories now dominate nearly all areas of historical inquiry—and for good reasons. Just look at the scholars assembled for our roundtable today. Consider Jon Sensbach’s landmark microhistory of Rebecca Protten, an Afro-Moravian woman who flourished in the West Indies and Europe; T.J.’s recent examination of almanacs reframes the study of religion around a critical genre of literature that was immensely popular on both sides of the Atlantic; Heather’s innovative approach to the “puritan Atlantic” and careful study of increasingly racialized religious bodies and their troubled relationship to the body of Christ; Adrian’s deep history of martyrology in Old and New England.[1] To this list we could add the recent works of Emily Conroy-Krutz, Kathryn Gin Lum, Christine Heyrman, Susan Juster, Carla Pestana, Erik Seeman, Mark Valeri, and many others who are contributing to the study of religion within the emerging paradigm of #VastEarlyAmerica.[2] And yet, despite these considerable gains, the field of early American religious history still lacks a definitive history of transatlantic popular religion. There are, as yet, no transatlantic heirs to David Hall’s Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment or Jon Butler’s Awash in a Sea of Faith.

To advance the field in this direction, we might consider taking a brief step backward—back to a critical moment late in the 1980s, when Butler, Hall, and other scholars were calling for historians to engage more deeply with European scholarship on popular religion. And here I’m thinking of Butler’s revisionist “Transatlantic Problématique” and “Historiographical Heresy” essays, as well as Hall’s several historiographical review articles on New England puritanism. During the years leading up to the emergence of “lived religion” as a conceptual framework in the mid-1990s, both scholars were challenging colleagues to study lay religiosity: things like comparative supernaturalisms; gender, family strategies, and the life cycle; healing practices; various conceptions of religious time (family or evangelical); and the “spiritual convictions of the unchurched and the ambivalently churched.” Their watchwords were syncretism, eclecticism, intermittences, horse-shed Christians. “We are challenged,” Butler pressed in 1985, “to write a history explicitly focused on the spiritual life of an entire population, not just of clergymen and prominent laypersons.”[3]

This was the issue that energized me when I began working on Darkness Falls on the Land of Light. Early in my career, I possessed a kind of arrogant, Annales school confidence in my ability to write a total history of the religious culture of eighteenth-century New England. (And, I suppose, that obsession helps to account both for the length of my book as well as the longue durée of its publication!)

But what if we returned to the Butler-Hall popular religion paradigm, blended it with a few regional insights from Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, and applied the results to Atlantic world history? What might such a future study look like? I’m not sure—and such a project is surely beyond my skill—but here are a few thematic issues that we might want to consider. Four, to be precise:

First, future students of transatlantic popular religion should probably steer clear of measuring religion by volume—either by the loudness of particular religious communities or by the sheer number of surviving sources in a given archive. Jonathan Edwards left behind an incomparable body of publications and manuscripts, but this fact alone doesn’t necessarily lead to the conclusion that he was a more effective or influential pastor than, say, his good friend Ebenezer Parkman, the unassuming minister of Westborough, Massachusetts, who carefully shepherded his congregation during his impressive six-decade pastorate.

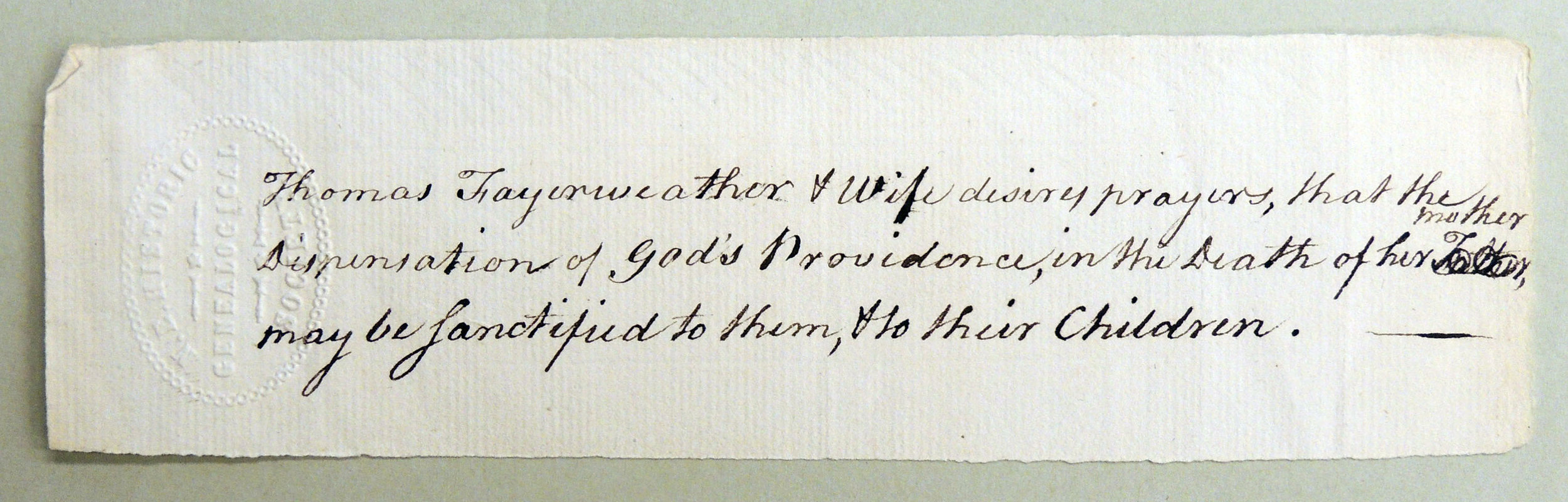

The godly walkers who inhabit Part One of Darkness Falls, moreover, were a pretty quiet lot. They weren’t especially anxious or concerned about salvation—whatever their Calvinist upbringing or puritan heritage. Neither were they rationalistic or unemotional, dull or formalistic, nominal or unchurched. Prayer bills are the classic godly walker texts: brief, patterned, regular, orderly. These people were far more concerned with the here and now of their religious lives. Indeed, one of my favorite quotes in Darkness Falls comes from a 1750 letter of thanks by a New Hampshire man to his parents for providing him with a rigorous religious upbringing. “God saith that the Children of the Righteous upon the account of their parent[s] have no more cause to hope for being Saved on that account than the Children of the wicked,” he admitted. Then he added, “but God reward[s] the Children of Righteous often times on account of their Parents tho’ not [with] Eternal Salvation yet with the good things of this Life.”[4]

So when the Whitefieldian revivals came and the people called New Lights began to rail against their unconverted, but godly walking neighbors and ministers, we should recognize such attacks for what they were: a formidable critique of a particular way of being religious, rather than evidence of “getting” religion altogether. The loudness of James Davenport and his considerable lay following doesn’t mean that they were somehow more religious than those whose beliefs, practices, and experiences they so vehemently criticized. To put things bluntly: I sharply disagree with Charles Grandison Finney’s famous claim that “A ‘Revival of Religion’ presupposes a declension.”[5] After all, from a historical numbers standpoint, it’s quite possible that New England’s era of great awakenings produced more Anglican conformists than Whitefieldian new converts between 1740 and 1770.

Here’s my second suggestion: the bible is important, of course, but it was much more than a book for eighteenth-century Protestants. We’ve grown accustomed to thinking of “biblicism” as a cornerstone of incipient transatlantic evangelicalism. For a half century prior to 1740, Congregational church admission relations (and, as a quick aside, it important to remember that these texts aren’t “conversion narratives,” as many scholars have assumed)…that these texts were studded with biblical quotations and allusions. More than one church membership candidate in Haverhill, Massachusetts, described the bible in conventional terms as a “perfect rule of faith and practice.”

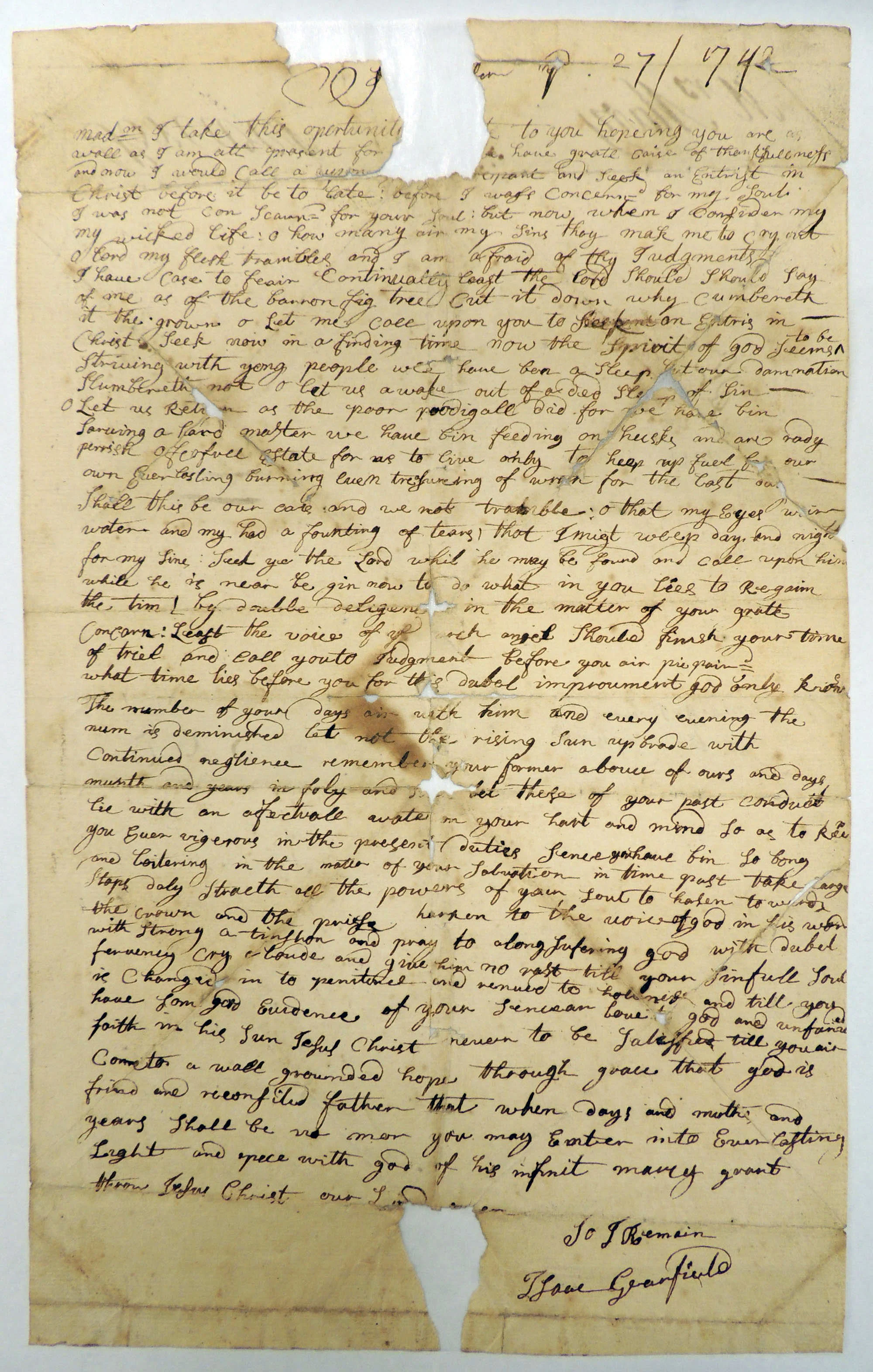

Yet something else happened over the course of the eighteenth century: Whitefieldarians began to experience the bible differently. Scratch any mid-century conversion narrative, from Sarah Osborn to Nathan Cole, or peruse the church admission testimonies from white hot revival communities such as Ipswich, Granville, or Middleborough, Massachusetts, and you’ll find lay men and women talking about “them words that came to me” during their darkest hour of distress. Of bible verses that “dropped” into their minds; “rained” on their souls; even “followed them around” as they pursued their daily routines. Nothing worried Jonathan Edwards more than his parishioners’ fascination with these unruly biblical “impulses” and “impressions.”

And this way of experiencing scripture—if we can use that phrase—grew increasingly elaborate as the century progressed. Within a decade of the Whitefieldian revivals, people began hearing composite biblical impulses: a string of unrelated verses patched together into a single message. “Them words” occasionally came from the hymns of Isaac Watts; some impulses that triggered the conversions of more radical New Englanders had no biblical referent at all.

Taking a page from Leigh Schmidt, I’d suggest that people heard the bible sounding in their minds as much as they read it—especially during the most transformative moments in their spiritual lives.[6] A transatlantic history of popular Christianity, therefore, should pay close attention to the role of biblical impulses in the spiritual narratives of, say, enslaved Africans or English Methodists. Not surprisingly, no statements were more often excised from the accounts of conversion taken down by Scottish pastors during the Whitefieldian revivals in Cambuslang, Scotland, than passages that began with the phrase “them words came to me.”

My third suggestion is this: theology, denominations, and ecclesiastical institutions count too, but the myriad ways in which people arrived at, conformed to, or rebelled against these sources of religious authority are probably more important. Or to restate the point in a somewhat different way, we need to think of the religious lives of lay men and women as becoming rather than being. Instead of defining puritanism or evangelicalism—or Methodism or Anglicanism—and then applying these definitions to one set of texts or another, we should consider routes into and, perhaps, through various religious traditions. This is not to say that formal theology isn’t important. But rather, as Butler and Hall maintained, we need to keep examining the ways in which religious ideas and institutions were embraced, resisted, reinscribed, or reshaped by lay men and women. This way of approaching the study of religion is deeply indebted to concepts such as Hall’s “family strategies”—the logic by which people affiliated with organized religious institutions at specific moments in the life course. It’s also one way to make sense of the pervasive metaphor of religious “travel” that the people I discuss in Part 5 of Darkness Falls used a synonym for experience.

Much of my book is devoted to tracing the paths of religious travelers. The godly walkers of Haverhill needed to take only a few relatively short steps to the place where they had always belonged: church membership in the Congregational land of light; but on the other side of the Whitefieldian revivals, the spiritual travels of Nathan Cole or Sarah Prentice lasted for decades and led them to religious worlds unimaginable to their young adult selves.

Lastly, I think we should resist the urge to reduce or translate the study of popular religion into other, seemingly more real or important, realms of history. Darkness Falls on the Land of Light is a book about religious experience—about the ways in which lay men and women in eighteenth-century New England learned to experience religion differently and the different, often competing, vocabularies, idioms, and story frameworks they inherited, devised, debated, and improvised to give shape and meaning to their worlds. I embarked on this project with a nagging suspicion that we needed a thicker description of what ordinary people experienced in their religious lives over the course of the long eighteenth century.

We know so much about the leading ministers of this period. Consider the sheer number of biographies written over the past half century from Edmund Morgan’s Gentle Puritan to George Marsden’s Jonathan Edwards.[7] And yet only a handful of well documented lay men and women stand for whole: Nathan Cole, Hannah Heaton, and, most recently, Sarah Osborn.[8]

And so the book that emerged from my reading of a wide array of understudied manuscript sources eventually evolved into a series of meditations on the languages of experience, of the bible as it was experienced as much as read, of visions and embodied presences of the Holy Spirit, and of the ways these kinds of experiences changed over the long eighteenth century. Only on a secondary level is Darkness Falls a book about the social costs of the changing religious experiences that I associate with the rise of Whitefieldian evangelicalism. Readers interested in learning about gender, or race, or politics may come away from the book dissatisfied.[9] Or they’ll need to take a further interpretive step (and I hope they will) to apply my readings of eighteenth-century popular religion to these and other historiographical agendas.

In our conversation today, we should definitely discuss the questions that Adrian Weimer and Jon Sensbach have proposed: what can the category of religious experience tell us about, say, transatlantic print culture or the American Revolution. I thought long and hard about the latter as I wrote, before concluding that I just didn’t have much to say about politics—or, to be more precise, that harnessing my argument to broader social forces would have obscured the broader point of the project.

But on another level, we should also think carefully about whether or not these are the questions that need answering, even at this current moment in our politics where the humanities are under siege and, perhaps in response, scholars feel compelled to advocate for the scholarly relevance of their work among a broader reading public.

Here, I’m reminded of Robert Orsi’s recent work on what he has provocatively called the “real presence” of the holy.[10] Orsi has challenged scholars to move not merely beyond the category of belief but also beyond the common tendency to translate or reduce religion to symbols, or power, or race, or any number of other, seemingly more “real” forces. For Orsi, the study of religion must engage head-on the often troubling claims of people who believe that the gods (or in the case of my book, Jesus and the Holy Spirit, in particular) are physically present agents in the world—that the gods make history as much as politics, or economics, or social structures.

Let me be clear here: I don’t think Darkness Falls comes anywhere near approaching the kind of radical new religious history that Orsi envisions. But getting the experiences of the laity right—or as right as we can—is a necessary first step. And it may well be the missing piece in our rapidly developing historiography of religion in the early modern Atlantic world.

Notes

[1] Jon Sensbach, Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, Mass., 2006); T. J. Tomlin, A Divinity for All Persuasions: Almanacs and Early American Religious Life, Religion in America (New York, 2014); Heather Miyano Kopelson, Faithful Bodies: Performing Religion and Race in the Puritan Atlantic, Early American Places (New York, 2016); Adrian Chastain Weimer, Martyrs' Mirror: Persecution and Holiness in Early New England (New York, 2011).

[2] Karin Wulf, “For 2016, Appreciating #VastEarlyAmerica,” Uncommon Sense—The Blog, Jaunary 4, 2015, https://blog.oieahc.wm.edamau/for-2016-appreciating-vastearlyamerica/ (accessed February 2, 2018).

[3] In addition to David D. Hall’s Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (Cambridge, Mass., 1989); and Jon Butler’s Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People, Studies in Cultural History (Cambridge, Mass., 1990); see Butler, “The Future of American Religious History: Prospectus, Agenda, Transatlantic Problématique,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 42 (1985): 167–183 (quotations 177–178); Hall, “On Common Ground: The Coherence of American Puritan Studies,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 44 (1987): 193–229; Butler, “Whitefield in America: A Two Hundred Fiftieth Commemoration,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 113 (1989): 515–526; Butler, “Historiographical Heresy: Catholicism as a Model for American Religious History,” in Thomas Kselman, ed., Belief in History: Innovative Approaches to European and American Religion (Notre Dame, Ind., 1991), 286–309; Hall, “Narrating Puritanism,” in Harry S. Stout and D. G. Hart, eds., New Directions in American Religious History (New York, 1997), 51–83; Hall, “‘Between the Times’: Popular Religion in Eighteenth-Century British North America,” in Michael V. Kennedy and William G. Shade, eds., The World Turned Upside Down: The State of Eighteenth-Century American Studies at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century (Bethlehem, Pa., 2001), 142–163; and Hall, ed., Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice (Princeton, N.J., 1997).

[4] Douglas L. Winiarski, Darkness Falls on the Land of Light: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2017), 79.

[5] Charles G. Finney, Lectures on Revival of Religion, 2d ed. (New York, 1835), 9.

[6] Leigh Eric Schmidt, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000), ch. 2.

[7] Edmund S. Morgan, The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles, 1727–1795 (New Haven, Conn., 1962); George Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (New Haven, Conn., 2003). For a list of similar works, see Winiarski, Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, 372, n. 8.

[8] Catherine A. Brekus, Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (New Haven, Conn., 2013).

[9] See, for example, Heather Kopelson’s recent critique of Darkness Falls on the Land of Light in the William and Mary Quarterly (75 [2018]: 194–198), in which she reprises her remarks at the ASCH panel.

[10] Robert A. Orsi, History and Presence (Cambridge, Mass., 2016), 8.