In my current research, I’ve been searching for sources that reveal how and why western settlers converted to Shakerism during the years following the Great Revival (1799–1805). The Shakers kept detailed records of all sorts, but most were written by the leaders of the sect. Few rank-and-file believers described their experiences, especially during the critical early years of the Shakers’ expansion into Kentucky and Ohio. Even fewer shared those experiences with the “world’s people”—the friends, neighbors, and family members they left behind.

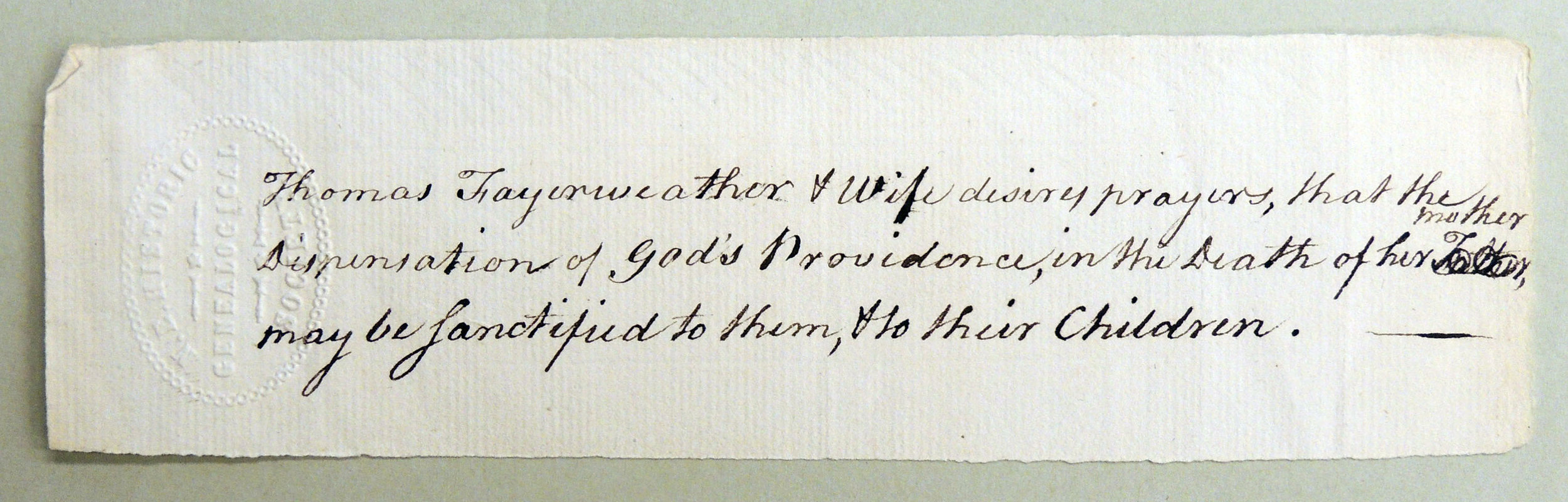

Shaker convert Caleb Callaway scrawled his signature on this 1829 financial agreement. Caleb Callaway, deed of gift to John C. Callaway, June 30, 1829, box 1, Shakers—South Union, Ky., Business and Legal Papers, 1769–1893, MSS 154, Manuscripts and Folklife Archives, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, Ky.

That’s what makes the following letter by Caleb Callaway (1761–1829) so valuable. Tucked away in one of the sprawling notebooks of John Dabney Shane, a nineteenth-century Presbyterian minister and amateur historian, is a brief note that Callaway penned to his brother-in-law, James French, during the summer of 1811. At the time, Callaway had been living for two years at the Gasper River (later South Union) Shaker village near Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Callaway provided a detailed exposition of the “faith and manner of life that I now live.” Like many western revivalers and recent Shaker converts, he believed he was living in an extraordinary new dispensation in which “Christ has made his 2nd and last appearance into the world.” Interestingly, Callaway did not associate Christ’s return with the figure of Shaker founder Ann Lee. But he did presume, as did all Shakers, that Christ was not a man but rather an inward principle, an “anointing of the Holy Ghost,” available to all of the “sons of God.” For those who crucified the flesh, gloried in the celibate “cross of Christ,” forsook all “natural relations,” and devoted themselves to the communal life of the Shakers, it was possible to “live a holy life” on earth “clear from sin, from day to day,” with a “peace & union the world knows nothing of.” And that choice was voluntary, as Callaway explained in the final lines of the letter. “Salvation is free for every soul,” he encouraged his brother-in-law, “they may choose or refuse it. All are free Agents as to that.” Utterly confident in the rightness of his new Shaker faith, Callaway proclaimed he would not “exchange my present situation, for the whole world.” He concluded the letter with an exhortation: “Come and see us, and know for yourself.”

Callaway’s crooked road to Shakerism began in what is now Bedford County, Virginia. He was born in 1761, the son of Richard and his first wife, Frances Walton. The elder Callaway had fought in the Seven Years War, and he later joined Daniel Boone in blazing the Wilderness Road to Kentucky. Caleb spent his early years at Fort Boonesborough, where he witnessed the capture of his sister and the death and mutilation of his father at the hands of the Shawnee. Early in the 1780s, Caleb sold his share in his father’s lands and lucrative ferry operation, returned to southwestern Virginia, and married Elizabeth Callaway, his first cousin once removed. He appeared regularly on the Virginia property tax rolls for Campbell County during the next two decades, slowly rising through the ranks of society as he accumulated material goods and enslaved servants. The Callaways had at least seven children between 1784 and 1802. Then, in 1804, Elizabeth died unexpectedly—“passed away to the Summerland,” according to later Shaker records—and Caleb vanished.

Some evidence suggests that Callaway moved his family to North Carolina. Or he may have fallen on hard times and sought refuge with relatives. But when he resurfaced in Ohio County, Kentucky, five years later, Callaway was a changed man. Like so many of his contemporaries, he had passed through the fires of the Great Revival and been transformed. According to Shaker missionary Benjamin Seth Youngs, who encountered him for the first time on June 1, 1809, Callaway had joined the Halcyon Church, one of the most peculiar religious sects of the early American republic. Founded around 1806 in Marietta, Ohio, by a quixotic prophet named Abel Morgan Sargeant, the Halcyons renounced the traditional Christian doctrine of the trinity, rejected Calvinism, and advocated universal salvation. Denounced as an imposter by his opponents, Sargeant claimed to communicate with angels; he traveled throughout the Ohio Valley with a group of twelve female apostles; and he exhorted his small group of followers to live “without sin” and “become so holy as to work miracles, heal the sick and live without eating.”

Following his encounter with Youngs and the Shakers, Callaway abandoned the Halcyons and moved with family to the newly organized Shaker settlement at Gaspar River in Logan County, Kentucky. The following year he wrote to James French explaining his new faith.

Callaway’s two-decade life among a Shakers was uneventful, although not without challenges. In 1815, he indentured his three teenage sons, John Constant, Henry, and William, to the believers at South Union, who agreed to provide food, lodging, education, and trade skills until the boys turned twenty-one. John Constant remained with the Shakers until his death in 1830, as did a daughter, Matilda, who lived into the 1880s. Caleb’s other two sons, along with their two older brothers, Elijah and Elisha, left South Union in 1818. Callaway occasionally traveled on business for the believers and worked in their various mill complexes. In 1827, he was listed among the 75 brothers and sisters of the “Junior Order” who were living in the East Family dwelling house. Callaway died on the morning of July 8, 1829, and was buried the following day in an unmarked grave in the Shaker cemetery at South Union.

Callaway spent his last years in the East Section dwelling house at South Union Shaker village, near Bowling Green, Kentucky. Isaac N. Young and George Kendall, “Sketches of the various Societies of Belivers in the states of Ohio & Kentucky,” 1835, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

At the end of his transcription, Shane noted that Callaway’s “spelling, & division of sentences” were “miserable.” Judging from Caleb’s shaky signature on a South Union financial document, Shane was right!

John Dabney Shane transcribed Caleb Callaway’s July 11, 1811, letter to James French into the second volume of his “Historical Collections” notebooks, which are now among the Draper Manuscripts of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin (12 CC 209–10). For Callaway’s life at South Union, see Harvey L. Eads, transcr., Shakers—South Union, Ky., “Record Book A (including Autobiography of John Rankin, Sr.),” 1805–1836, 102, 265, 452, Shakers of South Union, Kentucky, Collection, 1800–1916, MSS 597, Manuscripts and Folklife Archives, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green; “South Union Graveyard Book,” 1750–1881, 2–3, typescript, III B:32, MS 3944, Shaker Manuscripts, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland. Information on Callaway’s notable father, Richard, is available in John E. Kleber, The Kentucky Encyclopedia (Lexington, Ky., 1992), 152. Adam Jortner briefly discusses the Halcyon Church in his recent Blood from the Sky: Miracles and Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville, Va., 2017), 164; see also C. E. Dickinson, A Century of Church Life, 1796–1896: A History of the First Congregational Church, Marietta, Ohio ([Marietta, Ohio], 1896), 31. On Shane and his “Historical Collections” notebooks, see Elizabeth A. Perkins, Border Life: Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1998), 15–24.

Gaspar River, Logan Co.

Friend James,

I have taken the privilege of writing to you my faith and manner of life that I now live. We believe that Christ has made his 2nd and last appearance into the world; and his errand is to save his people from their sins, and to destroy that nature that is in man, that is not subject to the law of God, & to bring in everlasting righteousness. The greater part of mankind h[as] b[een] expecting Christ to come in the shape of a man. I answer nay; the Church of Xt had its foundation in the revelation of God; and that foundation is Christ. But who or what is Christ? The name of Christ signifies the anointed, and arose from that spiritual unction, or anointing of the Holy Ghost, w[ho] [with] Jesus was anointed to preach the Gospel of Salvation to the [poor]. And I, as well as many others, have read: Christ, and as many as recieve him, to them he gives power to become the sons of God.[1] And we [heed] him by honestly confessing our sins to God before God’s witnesses. This I have done, and I now live a holy life from day to day; taking up the cross of Christ, self-denial, working out my salvation, forsaking all natural relations, that is, that is, that spirit that they are of, that stands against God. I love their persons & their souls, but not that carnal nature. Neither does God love it. I do know that I live clear of sin, from day to day; And I have that peace & union that the world knows nothing of. Nor wo’d I exchange my present situation, for the whole world. I do know that I have peace with God, and I know I am not decieved. To know God, & Jesus Xt whom he has sent, is eternal life, and nothing short of this is Eternal life. We have the everlasting Gospel w[ith] us, that saves people from their sins. And the Tabernacle of God is with men, and the judgment is set. And I have sent my sins into judgment beforehand, and judgment is given to the saints. This is that work that God promised long ago to bring about, by the prophets and Apostles. A strange work, and strange it is. And I can say as Paul did, I am crucified to the world, and the world to me. And I glory in the cross.[2] And I die daily unto sin, and live to God, putting on the Lord Jesus Xt, and making no provision for the flesh to fulfil it in the lust therof.[3]

Come and see us, and know for yourself. By the fruits you are to know them.[4]

I suppose my old mother is gone out of the body, is she not?[5] Tell Keeza and all the children, that salvation is free for every souls on the earth: either in the body or out of it, all will have a chance to come in.[6] And they may choose or refuse it. All are free Agents as to that. I add no more at present, but remain your friend,

Caleb Calloway

July 11th 1811

To James French, Montgomery Co., Ky.

(Post-mark, “Frankfort, K. July 11th.”)

(The spelling, & division of sentences, miserable.)

[1] John 1:12.

[2] Cf. Gal 6:14.

[3] Cf. Rom. 13:14.

[4] Cf. Mat. 7:20.

[5] Callaway’s stepmother, Elizabeth (Jones Hoy) Calloway (1733–1813), lived with French and was still alive in 1811. She is buried in the French family cemetery near Mount Sterling, Ky.

[6] “Keeza” was Callaway’s sister, Keziah (Callaway) French (1768–1845), who married James French and lived in Montgomery County, Kentucky.

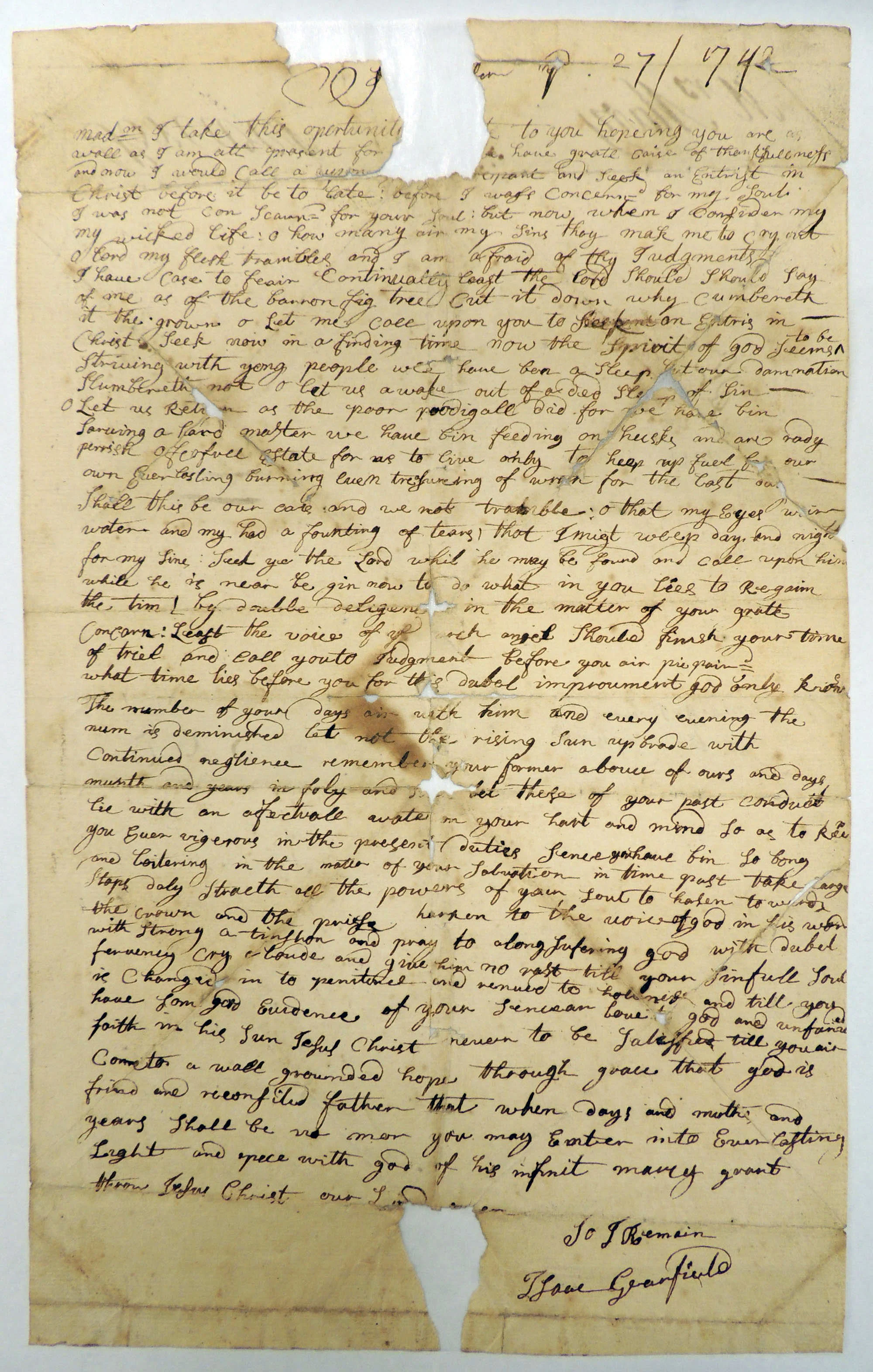

John Dabney Shane’s transcription of Caleb Callaway’s 1811 letter to John French. Kentucky Papers, 12 CC 209–10, microfilm, Draper Manuscripts, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison.