Darkness Falls on the Land of Light is now available in paperback. Happy reading!

Of Whores & Witches, Rakes & Hell Hounds (Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1743)

Sometimes even a single manuscript I stumbled across while researching Darkness Falls on the Land of Light overturned everything I thought I knew about New England’s era of great awakenings. Consider the stunning letter (below) by Joseph Higgins, a coastal trader and merchant from Old Lyme, Connecticut.

In 1743, Higgins dispatched this strident missive to an unnamed clergyman. The recipient was likely Charles Chauncy, Boston’s vociferous opponent of the Whitefieldian revivals. Higgins was aiming to blow the whistle on his own minister, Jonathan Parsons. The letter contains a petition in which several parishioners in the Lyme Congregational church accused Parsons of nearly three dozen theological and ecclesiastical errors.

Here’s the unusual part: Parsons ranked among the most successful and respected ministers in eighteenth-century New England. Historians frequently point to his published account of the religious stir in Lyme—which was serialized in an evangelical magazine called the Christian History—as the paradigmatic revival narrative of the colonial era. In later years, Parsons presided over one of the largest congregations in New England: Newburyport’s Old South Presbyterian Church, the final resting place of George Whitefield himself.

But the figure in Higgins’s letter is nothing like the temperate clergyman of revival literature. Parsons abandoned all decorum in his church services and opened his pulpit to an array of gifted lay people. He brazenly declared that whores, witches, rakes, and hell hounds would find their way to heaven long before the “old Gray hedded” communicants his church. One of the aggrieved brethren even recalled hearing Parsons gloat that he would stand as a witness against unconverted sinners on the Day of Judgment; and he prayed aloud that hellfire might blaze out of their mouths. Most ominously, the Lyme minister zealously endorsed the “Enthusiastick Doctrines & Practices” of the most incendiary New Light itinerant of the era, James Davenport.

After discovering Higgins’s extraordinary letter, it took me several years to piece together the entire controversy. The search lead me first to the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston; then to the Connecticut Conference Archives of the United Church of Christ in Hartford, the Library of Congress in Washington, and the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan; and finally to a unique cache of church papers at the Florence Griswold Art Museum in Old Lyme.

The Lyme controversy is one of my favorite sections of Darkness Falls. It’s a powerful example of the social and ecclesiastical costs of the Great Awakening—something scholars have been slow to acknowledge. Even still, the story of Lyme’s checkered religious history was quickly forgotten. Early in the twentieth century, artists and literary recast Lyme as the quintessential New England village. Immortalized in the vibrant colors and bold brushwork of American impressionist Childe Hassam, the Congregational meetinghouse emerged as an icon of simpler times, a pre-industrial community bound together by town and church.

Joseph Higgins knew better.

Higgins’s 1743 letter to an unidentified clergyman is part of the collections of the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston (Mss. C 1345). For a detailed analysis of the Lyme controversy, see Darkness Falls on the Land of Light: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2017), 333–352. Jonathan Parsons published his “Account of the Revival at Lyme West Parish. . .” in Thomas Prince, Jr., ed., The Christian History, Containing Accounts of the Revival and Propagation of Religion in Great Britain & America (Boston, 1744), 118–162 (for excerpts, see Alan Heimert and Perry Miller, eds., The Great Awakening: Documents Illustrating the Crisis and Its Consequence [Indianapolis, Ind., 1967], 35–40, 187–191, 196–200). Additional documents relating to the Lyme revival appear in Richard L. Bushman, ed., The Great Awakening: Documents on the Revival of Religion, 1740–1745 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1969), 40–42, 53–54. See also the Records of the New London Association, 1708–1788 (available online at the Congregational Library’s New England’s Hidden Histories: Colonial-Era Church Records New England's Hidden Histories digital archive).

Lyme 1743

Reverend Sir.

At your Request I have undertaken to Give you an Account of the Doctrine & Conduct of the Minister & People of this Place & I have Thought Best to Give you a Coppy of a Complaint Exhibited Against Mr. Parsons by Capt. Timothy Mather in the following things:

1. With Approving Attending & Encouraging Separate Meetings for Religious Worship.

2. With Allowing Approving & Encouraging Persons when moved with Imperssions (that are Common Among us) to Cry out with a loud voice in the Time of Divine Worship to the Disturbance of the Worshipping Assembly.

3. With Inviting & approving Unqualified Persons to preach & to Exhort the People such as Thacher Prince &c.

4. With Breaking Covenant with this people by Going to Long Island, to preach without any Necesary Call, when he knew the Church was in Great Danger of being led away from the Simplicity of the Gospel by the Enthusiastick Doctrines & Practices of Mr. Davenport.

5. With Recommending a Theif (Prosecuted found Guilty & [Recorded]) to the Charity of a Neighbouring Church without any Christian Satisfaction, tho he well knew the whole Matter.

6. With using his Endeavours to Admit a Baptist that had Apostatised from her Profession to Occational Communication with this Church.

7. With making an Unscriptural & unwarrantable Difference between Chirch Members of a Good standing in the Church by Giving the Appelation of Dear Brothers to Some & not to others (the new Lights are the Dear Brothers).

8. With Admitting Persons into the Communion of the Church that are Grossly Ignorant of the Principles of Religion &c.

9. With forbiding unconverted Persons to sing the 23 Psalm & such like Psalms.

10. With Publickly declaring Persons are converted Immediately upon their Experiences of these things, viz.: Distress & Terror of Conscience for Sin & their being afterwards filled with Joy, &c.

11. With Callumniating the Civill Authority (both in prayer & preaching) by Intimating that many of their Dictates are Unlawfull & unjust to be Imposed upon a Christian people terming of them Tyranny & a Bloody Inquisition &c. Praying that they people might not submit in Matters of the least Indifference.

Farther Capt. Mather laid these following Articles of false Doctrine, viz.:

1. That we have no Reason to think a man in a Goodd State let his life be never so Seemingly Religious, or Moral until he hath told his Experiences alledge its as a just Inference from our being, by Nature, Children of Wrath.

2. That an External Conformity to the Gospel is no Evidence that a person is a True Christian.

3. That multiplied acts of Gross Sins, yea sins of the Grossest kind is no Arguments or Evidence against a State of Grace.

4. That all Doubting in a Christian of his Good state was from the Devil.

5. That there is more hopes of a profane Swearer, Sabbath Breaker, Drunkard, whoremaster, going to heaven when he dies than that he will, that lives an honest Life & Strives to Serve God as well as he Can.

6. That he knows not but God might Save a Moral man but an hundred to one if he did for it was out of his usual way to save such.

7. He told us in a Sermon from Luke 14:13 that Christ Chose Sailors the worst of men to be his Companions, Highway & hedge Sinners a Company of Whores & Witches. That there was more hopes of a Rake Hell & hell hounds than Moral men & many things of the like Import &c.

8. That if he could get all the people to do nothing towards their Conversion he should not doubt but that they would all be converted in one Month.

9. That if God should Discover his glory to an unconverted person it would cause Hell in his soul & that hell flames would Blaze out of his mouth.

10. For a Person to Infer his Justification from his Sanctification was a Proof that Pharisees & Hypocrites have of their Justification.

11. That a Person Could draw no true Comfort to his own Soul when he does Justice, loves mercy, & walks humbly with God.

12. That he had often heard of a Humble Doubting Christian but never saw one that was a Humble Doubting Christian but was a Mear Chimera in Religion, an Imaginary Monster made up by Hypocrites & an Absolute Contradiction, a thing that never was nor can be & Such as Dream of Humble Christians Doubting were filled with pride & Opposition to God.

13. That Continued acts of Grose Sins of the Gosple Sort was no Evidence of a State of Nature or Sin & Death.

14. That St. Ambrose Says that to Call the Works of God the works of the Devil is the Sin against the holy Ghost though Ignorantly so Called.

15. That this is the Sin against the Holy Ghost (1) when Persons have Greived away the holy Spirit (2) turn again to Sin like a Dog to his vomit or the washed Sow &c. (3) Got to a heigher degree of Sin than before and then prayed oh that God would cause Some one now in this Assembly to Roar out to be a warning to others & that the Flames of hell might blaze out of all their mouths, for he knows of no Rule in the word of God to pray for Such.

16. That a Hypocrite may love God with a Sincere love.

17. That we had as much Reason to think Mr. Davenport was an holy Man as we have to think Peter James & John were.

18. In his Sermons he often tells us in an Angry manner I will Increase your Damnation in hell. I Expect to be a Witness against the Worst of you in the Day of Judgment, Though you have set under the Gospel 40, 50, 60 years the Bottom of hell I expect will be paved with the Soulls [Sculls?] of the most of you. You Cursed old Gray hedded Pharisees & Hypocrites &c. You Damn’d men & Damn’d Women &c.

19. You are Guilty of Adultery in the house of God. [You] Commit adultery in the Time of Divine Worship.

20. That in Conversion there is a Phisical Change that Conversion was one thing & Regeneration is Another.

21. The holy kiss Spoken of by the Apostle was meant in a Carnal Manner.

22. In opening them words, Judge not least ye be judged, he told us if he knew what the Rash Judging there meant was, it was Judging men converted before they had told their Experiences.

23. That the Apostle John had the Spirit on the Lords Day, but we read no more of it & we have Reason to think that the Spirit left him, without any more Returns.

24. It is no matter what Religion we are of if we beleive in Christ.

25. That if we have not Sensible Acts of Faith in Divine Worship we have not the Presence of God.

26. Forbids his hearers to read any of Dr. Tillitsons Works the whole Duty of man, & many others Authors & says that the Peice Entitled the French Prophets is the Cursedest piece of Stuf that ever was raked together on this hole Hell.

27. With speaking contemptuously of the Ministers of Former & Latter Days in saying these Churches have been Stuft with Damnable Stuff these 30, or 40 years & that the Substance of the Doctrines for 40 years past was such Cursed & Damnable Stuff.

28. That in Conversation a Man repents of all Sin both past & future & that Repentance is not necessary after Conversion.

29. That a person may Commit Gross acts of Sin such as fornication & Adultery having Grace in Exercise, yea that Grace in exercise sometimes prompts men to Sin.

30. When a Person was crying out in the meating house after service said Mr. Parsons you that are Dissatisfyed Go & take the words of the holy Ghost from that mans mouth.

31. That we have as much reason to beleive the Present work is the work of God as we have to beleive the Mission of Christ.

In the next place Capt. Mather Charges Mr. Parsons Prayers with being unwarrentable in these things:

1. Praying for the Miraculous Gift of Tongus (2) that Unconverted ministers may be converted or put out of the Ministry (3) that God would Appear in as Visable a manner as at that Memorable Sacrament when there was Crying laughing & talking even every thing [allmost] Imaginable.

These sir are the things Laid in against Mr. Parsons & there is no Doubt but they will be proved and many such more might be added. There are many meatings in this place where there is all these things acted in the mean time, Viz.: Singing Praying Groaning Exhorting laughing & Talking in the same Room & all manner of noises that may be Imagined &c. & one thing more I will mention that is, we may Command God the whole of his Kingdeom &c. & now Sir please to Send me your Opinion on these matters from your friend & Servant,

Joseph Higgins

But Sir Mr. Parsons hath been well satisfy’d for 4 years. But this Day we had a Meeting & now he Demands £320—£350 in the Room of £240: though a very holy man & quite left of[f] Caring for this Worlds Goods.

P.S. I had the Request by my kinsman Mr. Israel Higgins known to yourself.

[Endorsed:] Charges Against Bishop Parsons

Reflections on Richmond's Historic Cemeteries

Ok, this post doesn't really belong on a blog about the People Called New Lights. But I was recently invited by the Richmond Times-Dispatch to reflect on "Richmond: City of the Dead," a material culture seminar I teach at the University of Richmond, and to share some thoughts on the plight of East End Cemetery, an important African American burial ground that has suffered from decades of neglect and vandalism. Here's a link to the interview, which also discusses the work of my colleagues in the East End Collaboratory. To learn more, check out the Collaboratory's innovative digital map of East End; Richmond Cemeteries, an interactive website created by Collaboratory member Ryan Smith (History, Virginia Commonwealth University); volunteer opportunities with John Shuck and the Friends of East End; and the haunting photographs and powerful essays of journalist and activist Brian Palmer.

Digital New Lights 2: New England’s Hidden Histories

Historians of religion in early America ought to be shouting “Huzzah!” for the Congregational Library these days. Since 2011, Jeff Cooper and a team of scholars at this important research archive on Boston’s Beacon Hill have been gathering at-risk Congregational church records from basements, bank vaults, and private homes. The goal of the library’s New England’s Hidden Histories project is stunningly ambitious: to preserve, digitize, and transcribe tens of thousands of pages of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century church records.

I’ve been fortunate to serve on the steering committee for the program, which is led by Cooper and the Congregational Library’s executive director, Peggy Bendroth. Many of the key manuscript collections cited in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light are now available online through the NEHH portal, while many others are coming soon.

Testimony of Hannah Corey, April 5, 1749, Sturbridge, Mass., Separatist Congregational Church Records, 1745–1762, Congregational Library, Boston (available online at NEHH)

Highlights from the NEHH collection (so far) include:

- More than 500 church admission relations from Haverhill, Middleborough, and Essex, Massachusetts—all in full, glorious color!

- Church records from the “praying Indian” church at Natick;

- Ministerial association record books from nearly every county in Connecticut;

- Lists of men and women admitted to the First Church of Ipswich, Massachusetts, site of one of the largest religious revivals of eighteenth-century North America;

- Minutes from the Grafton, Massachusetts, church record book, with transcription, detailing the troubled pastorate of the ardent revivalist clergyman Solomon Prentice and his separatist wife, Sarah;

- Disciplinary records resulting from the bitter New Light church schisms in Newbury and Sturbridge, Massachusetts;

- Miscellaneous church papers from Granville, Massachusetts, featuring letters by the celebrated African American preacher Lemuel Haynes;

- And a wide range of sermons, theological notebooks, and personal papers by eighteenth-century Congregational clergymen, including luminaries Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards, and Samuel Hopkins.

Cooper and Bendroth have forged partnerships with New England’s leading history institutions, including the American Antiquarian Society and Peabody Essex Museum. And they have digitized An Inventory of the Records of the Particular (Congregational) Churches of Massachusetts Gathered 1620–1805, the indispensable guide compiled by Bendroth’s predecessor, Harold Field Worthley.

For teachers eager to show their students what seventeenth- and eighteenth-century history is made of; for undergraduate and graduate students seeking primary texts for papers; for genealogists searching for baptismal records of long-lost ancestors; for scholars engaged in major book projects—NEHH is now the go-to hub for online research on the history of New England puritanism and the Congregational tradition.

As with all digital history initiatives, NEHH is a work in progress. They’re always looking for volunteers to support their crowd-sourced transcription projects. It’s a great opportunity to involve students in the production of new historical knowledge. For more information, contact Jeff Cooper or Helen Gelinas, director of transcription.

Thanks to a second $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Bendroth, Cooper and their colleagues at the Congregational Library will be churning out high quality digital images and transcriptions of rare Congregational manuscript church records for years to come. Congratulations, CLA! Huzzah!

To read more about the NEH grant, check out this article from the Christian Science Monitor.

Edwards at Enfield (July 1741)

Jonathan Edwards’s Sinners in the Hand of an Angry God ranks among the most frequently studied and anthologized sermons in American history. But how successful was his storied performance at Enfield, Massachusetts (now Connecticut), on July 8, 1741?

Stephen Williams, the Congregational minister in the neighboring parish of Longmeadow, famously noted in his diary that Sinners elicited a dramatic outpouring of emotions and bodily exercises among the Enfield assembly. Edwards’s fiery imagery and vertiginous metaphors—especially the “loathsome” spider dangling over the flames of hell—ignited a wailing din of screaming and sobbing that filled the Enfield meetinghouse. The deafening noise was so “piercing & Amazing,” Williams remarked, that the Northampton evangelist was “obliged to desist.” Edwards never finished his “most awakening Sermon.”

Detail from Thomas Jeffrys, A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of New England ([London], 1755). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress (available online).

And we also know that Sinners was part of a coordinated effort among the ministers of the Connecticut Valley to engineer what Williams called “the revivle.” Edwards spent nearly a week in the surrounding towns before preaching at Enfield. A few days earlier, he had celebrated the sacrament across the river in Suffield, where he delivered several equally potent sermons and admitted 95 men and women to full communion. Meanwhile, Joseph Meacham of Coventry, Benjamin Pomeroy of Hebron, and, especially, Eleazar Wheelock of the “Crank” parish of Lebanon (now Columbia), Connecticut, worked their way up and down both sides of the river north of Hartford. Everywhere they went during the first week of July, their powerful revival sermons on the necessity of conversion provoked “considerable crying among the people,” “shakeing & trembling,” and “Screaching in the streets.”

Although the Enfield Congregational church records have not survived, evidence from nearby parishes suggests that the collective efforts of Edwards, Wheelock, and their colleagues were extraordinarily successful. Hundreds of lay men and women joined Congregational churches throughout the region during the summer of 1741. And these young coverts were only the tip of the iceberg; perhaps three times as many existing church members began questioning their past spiritual lives. A little over a month after the Connecticut Valley revivals blazed to life, Edwards’s father reported to Wheelock that “Religion hath been very much revived and has greatly flourished" in his East Windsor parish. "There are above seventy, that very lately…have been savingly converted in this society, and still there is a great stir among us.”

What was his son’s contribution to this extraordinary harvest of souls? How many people claimed to have experienced conversion after hearing Edwards's performance of Sinners in the Hand of an Angry God? Misfiled for more than a century and published below for the first time , a letter written by Wheelock three days after the “Great Assembly At Enfield” provides the definitive answer. Given Edwards’s exploits at Suffield, Stephen Williams’s extraordinary diary entries, and his father’s glowing report the following month, Wheelock's figure seems oddly underwhelming: “ten or twelve Converted.”

Eleazar Wheelock’s undated letter to his parishioners in the North (or “Crank”) Parish of Lebanon may be found among the Eleazar Wheelock Papers, no 743900.1, Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College Library, Hanover, N.H. The missive bears a notation on the verso side in a later hand that reads “to his people at Lebanon 1743”; but the details indicate that he composed it two years earlier, on July 11, 1741.

For a detailed analysis of Edwards’s itinerant activities in the Connecticut Valley during the summer of 1741, see Douglas L. Winiarski, “Jonathan Edwards, Enthusiast? Radical Revivalism and the Great Awakening in the Connecticut Valley.” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 74 (2005): 683–739 (click here to download from JSTOR); and Darkness Falls on the Land of Light: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2017), 222–225.

The definitive edition of Sinners in the Hand of an Angry God (Boston, 1741) appears in Jonathan Edwards, Sermons and Discourses, 1739–1742, vol. 22, Works of Jonathan Edwards, ed. Harry S. Stout and Nathan O. Hatch with Kyle P. Farley (New Haven, Conn., 2003), 400–435. A typescript edition of Stephen Williams’s diary produced during the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration is available online at the Richard Salter Storrs Library, Longmeadow, Massachusetts (see volume 3, pages 375–379, for his famous description of Sinners and subsequent events in Longmeadow and Springfield described in Wheelock's letter). The extract from Timothy Edwards’s letter to Wheelock quoted above was published in William Allen, “Memoir of the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, D. D.,” American Quarterly Register 10:1 (August 1837): 12.

To the Church and People of God in Lebanon North Parish

Dearly Beloved,

I Came here to Winsor yesterday with a Design to Come to you this Day. The Lord Bowed the heavens and Came Down upon the assembly the Last night. The house seamd to be filled with his Great Power, a very Great Number Crying out under a sence of the wrath of God and the weight of their Guilt, 13 or 14 we Beleive Converted. My Dear Brother Pomeroy Came to me this morning from Mr. Mash’s Parish where the work was allso Great the Last night. We were Just setting out to Come home but a Number of people were met together and the Distress among them soon arose to such an heighth that we think we have a Call of Providence to Continue here over the Sabbath. Several have been Converted already this morning. There is now work Enough for 10 Ministers in this town & there is a very Glorious Work att Suffield And it was very marvellous in a Great assembly At Enfield Last Wednesday, ten or twelve Converted there. Much of his power was Seen at Longmeadow on Thursday, 6 or 7 Converted there and a Great Number wounded. There was Considerable Seen at Springfield old town on Thursday Night and much of it again yesterday Morning at Longmeadow. People Everywhere throng together to hear the word and I do verily beleive these are the beginning of the Glorious things that are Spoken Concerning the City of our God in the Latter day. I am much Concernd for Some that Remain yet Stupid and Blind. Among my Dear flock I Desire your Continual Remembrance of me your poor pastor in your prayers to God that I may be Strengthned in the inward & outward man to all that the Lord shall Call me to. I hope to be with you at the beginning of next week.

I am Your souls Friend & servant for Christ,

Eleazar Wheelock

Eleazar Wheelock to the North Parish Church, July 11, 1741. Courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.

Shakers & Jerkers (Greenville, Virginia, 1805)

The Journal of East Tennessee History recently published the first of a two-part series of articles in which I chronicle the Shakers’ epic “Long Walk” from New York to Ohio in 1805. Part travel narrative, part missionary report, Shaker letters from the Long Walk shed new light on the controversial “bodily exercises” that dominated accounts of the Great Revival (1799–1805). Centered in the Kentucky Bluegrass Country, this powerful succession of Presbyterian sacramental festivals and Methodist camp meetings played a formative role in the development of early American evangelicalism and the emergence of the southern Bible Belt. The Shakers were eyewitnesses to some of the most bizarre spectacles associated with the western revivals.

"The Jerks," Virginia Argus (October 24, 1804). Image courtesy of the Library of Virginia, Richmond.

Spurred by a newspaper report describing an outbreak of the strange somatic fits known as “the jerks” in the remote village of Abingdon, Virginia, Shaker leaders in New Lebanon, New York, dispatched three missionaries to investigate the Great Revival and gauge the prospects for evangelizing the western settlements. At the time, sectarian followers of British émigré Ann Lee, the “Elect Lady” and purported second coming of Christ in female form, had achieved widespread notoriety for their perfectionist theology, celibacy, pacifism, communal villages, and, especially, ecstatic dancing practices. Early descriptions of the Shakers “laboring” worship, as they called it, bore a striking resemblance to accounts of the bodily exercises of the western revivals.

Leading a packhorse encumbered by a large portmanteaux and bearing printed copies of a strident letter proclaiming the Shakers’ millennial new dispensation, John Meacham, Issachar Bates, and Benjamin Youngs set out on New Year’s Day, 1805. For more than two months they struggled through some of the worst winter weather of the nineteenth century. The Shaker missionaries traveled more than 1,200 miles south through New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, then up the Great Valley of Virginia, through East Tennessee, over Cumberland Gap, and into the Kentucky Bluegrass country—the heart of the Great Revival. By March 1805, the trio had reached the small settlement at Turtle Creek near Lebanon, Ohio.

Clover Mount (Robert Tate Homestead), Greenville, Virginia, ca. 1803. Image courtesy of the Virginia Department of Historical Resources, Richmond.

Along the way, the Shaker missionaries were keen to meet with Scots-Irish Presbyterian “jerkers”—men and women who had experienced unusual somatic fits during powerful revival meetings. As they passed through Greenville, Virginia, Meacham and Youngs spent an afternoon interviewing members of the family of Robert Tate, a prosperous Presbyterian elder, Revolutionary War veteran, and slaveowner, about their experiences with the jerks. The record of that conversation, carefully recorded by Youngs in a letter, is arguably the most detailed account of the bodily exercises of the Great Revival ever written. Although the Shaker missionaries moved on from Greenville, they continued to encounter “jerkers” like the Tates throughout the western settlements. Within a few years, hundreds of these radical “revivalers” and their families had converted to Shakerism and gathered together in a network of five communal villages that the missionaries organized in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana.

“Shakers & Jerkers, Part 1” presents an edited transcription of the missionaries’ January 31, 1805, letter, in which they narrated their progress from New York to Virginia and reported their encounter with the Tate family. Scheduled for publication in the 2018 volume of the Journal of East Tennessee History, the second installment in the series will cover the Shakers’ travels through Tennessee and Kentucky, as well as their early efforts to spread the gospel in southern Ohio. It also includes an unforgettable account of a Presbyterian society meeting in East Tennessee in which Meacham, Youngs, and Bates witnessed not only the jerks, but trance walking and other unusual somatic phenomena.

For colleagues seeking new readings for their courses on early American religious history, “Shakers & Jerkers” provides a vivid portrait of popular religion in the trans-Appalachian west. Graduate courses might effectively pair these edited Shaker texts with prominent studies of the Great Revival and southern evangelicalism: John Boles, The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt (1972; Lexington, Ky., 1996); Paul K. Conkin, Cane Ridge: America’s Pentecost (Madison, WI, 1990); Christine Heyrman, Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt (New York, 1998); Leigh Eric Schmidt, Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism, 2d ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich., 2001); or Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from Wesley to James (Princeton, N.J., 1999). Readers interested in learning more about the Long Walk and western Shakerism should begin with Stephen J. Stein’s definitive Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers (New Haven, Conn., 1992); see also Carol Medlicott’s excellent biography, Issachar Bates: A Shaker’s Journey (Hanover, N.H., 2013).

A New Relation (Boston, 1757)

Church admission testimonies, or “relations” as they were called, form the bedrock of my argument in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light. They afford one the best means of gauging broad changes in popular religious experience in early New England. I’m always on the lookout for examples of this distinctive genre of puritan devotional literature. Recently discovered by a researcher at the Congregational Library, the 1757 relation of Lydia Bourk of Boston’s First Church opens up some intriguing research questions.

Read MoreEarly American Religious History Syllabi

With the spring 2018 semester only a week away, I thought it might be interesting to post some of the syllabi for the courses I teach in the Religious Studies Department and American Studies Program at the University of Richmond: American Gods; Devil in the Details; Occult America; Native American Religions; Witchcraft & Its Interpreters; Cults Communes & Utopias in Early America; and Richmond: City of the Dead. Check 'em out and share your thoughts!

Old Light on George Whitefield (Middletown, Connecticut, 1740)

Nathan Cole’s wild ride to Middletown, Connecticut, is one of the best-known narratives in early American religious history. A late addition to his “Spiritual Travels” autobiography, Cole’s account of the “angelical” George Whitefield—“Cloathed with authority from the Great God” and preaching from a makeshift stage amid a throng of nearly 4,000—easily ranks among the most detailed descriptions of the celebrated Anglican evangelist’s first American tour. Whitefield’s revolutionary transatlantic ministry later incited bitter controversies, but in 1740 Cole and nearly everyone else in New England portrayed the traveling itinerant in glowing terms—everyone, that is, except John Osborn. His November 17, 1740, letter to his father, Samuel, a former Congregational clergyman, provides a fascinating counterpoint to Cole’s euphoria.

Osborn opened the letter with epistolary banter typical of a figure of his social rank: reports of the comings and goings of prominent local residents and merchants, requests for news of family members, and lamentations about money. Hidden within these seemingly mundane details, however, are important clues that reveal the aspiring physician and recent Harvard graduate’s evolving theological sensibilities. Osborn’s literary recommendations reflected his concern for religious moderation; references to Charles Chauncy, William Hooper, and Benjamin Kent place him among New England’s emerging liberal, or “Arminian” faction of clergymen. In the wake of his father’s dismissal from the Congregational church in Eastham, Massachusetts, in 1738, Osborn shared news of employment opportunities within New England’s rapidly proliferating Anglican churches. Within a year of Whitefield’s visit, Osborn had emerged as a “favourer of the principles of the church of England.” Ezra Stiles later described him as a “learned man” and “Deist.”

Osborn greeted Whitefield with contempt. He believed that Whitefield’s sermon on the dangerous of hell had infected his neighbors with a “contagious” passion. “When one was frighted,” the Middletown physician observed, “another catch’d the fright from his very looks, and others from these till the disease had Spread thro’out; and yet no one knew how he was frightened.” Whitefield’s vaunted oratorical skills amounted to little more than a “heap of confusion Railing, Bombast, Fawning, and Nonsense.” Even the noted early eighteenth-century Quaker preacher, Lydia Norton spoke in public with greater skill and power. Osborn’s caustic letter is an early indicator of the changing tenor of religious discourse in New England, which quickly rose to a boil during the months following the Grant Itinerant’s 1740 preaching tour.

John Osborn’s November 17, 1740, letter to Samuel Osborn may be found among the collections of the Boston Public Library (Ch.A.4.6). The illustrations below appear by permission. Nathan Cole’s account of Whitefield’s preaching in Middletown has been published in numerous early American history anthologies; for the definitive scholarly edition, see Michael J. Crawford, ed., “The Spiritual Travels of Nathan Cole,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 33 (1976): 89–126. I discuss both texts in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, 137–138. For biographical information on John Osborn, see John Langdon Sibley et al., Sibley’s Harvard Graduates: Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College, with Bibliographical and Other Notes, 18 vols. (Cambridge, Mass., 1873–1999), 9:551–554. The Stiles quotations appears in Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., Extracts from the Itineraries and Other Miscellanies of Ezra Stiles, D.D., LL.D., 1755–1794 (New Haven, Conn., 1916), 395. J. M. Bumsted sketches Samuel Osborn’s troubled ministerial career in “A Caution to Erring Christians: Ecclesiastical Disorder on Cape Cod, 1717 to 1738,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 28 (1971): 413–438. On Lydia Norton, see Rebecca Larson, Daughters of the Light: Quaker Women Preaching and Prophesying in the Colonies and Abroad, 1700–1775 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2000), 278.

Middleton November 17th 1740

Honour’d Sir,

I, about fourteen days Since, received yours of October 20th; by which we heard of your health and arrival at Boston. Mr. Doane got home last Saturday leaving his Sloop at Seabrook, the River being froze up. We are, and have been, generally in good health, Since I was at Boston. You desired me in your letter, to explain myself about wishing you to come to Connecticut this Fall; We Shou’d have been glad to See you, but besides Doctor Morison told me he thought he could get a place very easily in one of the inland towns where you might predicare and have a very good opertunity besides, to practice physic; and that he Should be glad to See and talk with you. My hint to John Avery arose from this, a little before he was here, a certain Clergyman of the established Sort told me that if I would go and assist him he would warrant me 40 or 50 pound per annum York money and a pretty good birth for a physician besides, only in assisting him I must precare & predicare, more Anglorum; he lives in a town which borders on the Salt water in York government; and I tho’t that if you liked you might have the Same offer; but I have not Seen the man Since nor heard from him tho’ I expect to every day.

The Famous Enthusiast Mr. Whitefield was along here making a great Stir and noise, tother day; tis a pretty amusement to observe how contagious that passion is, Just as their fear was in the meeting house in Boston when So much mischief was done with rushing out; when one was frighted, another catch’d the fright from his very looks, and others from these till the disease had Spread thro’out; and yet no one knew how he was frightened, nor what he was afraid of. I having Seen Several of his printed Sermons before, his discourse came out exactly according to my expectation, a heap of confusion Railing, Bombast, Fawning, and Nonsense. But expecting to See & hear good Oratory, I was basely cheated unless distorted motions, Grimaces, and Squeaking voices be good Oratory. For my part I Esteem Lidia Norton both an abler Orator & Sermonizer than him, and I have Seen her put as great a proportion of her audience in tears; though her pains are taken for far less profit than his. I want to know how Mr. Chauncy, Mather, Hooper, and Condy, affect him; but I believe tis hard to know, the Opinion of the Mob, and the danger of Loss of bread interposing.

I wish you had opertunity this winter to read Shaftesbury’s Characteristicks. Mr. Avery or Mr. Kent will help you to them; he was a man less afraid of Speaking truth than allmost any I have been aquainted with.

About Money, I want it very much myself Just now, and find it very difficult getting it where tis due to me; but I will do the best I can to pay my debts. I want to Know where Samuel and Joseph are; And whither Mr. Lord at Chatham loves me any better than he used to.

Our duty to Mother, and love to all friends.

I hope you will be So good as to write very Soon to us, at the Sine of the Lamb or White Horse you may find Connecticut people. Your book of Sermons I have Sent, and Shall be glad of the Greek lexicon if you can Spare it, & Tully’s Orations.

I wish you would read the [36th] book of Justins Hystory.

Your gratefull Son

J. O.

Out of the Fold (Westborough, Massachusetts, 1743)

Stephen Fay (1715–1781) is hands down my favorite character in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light. Eclectic and pugnacious, he’s a paradigmatic representative of the people called new lights. The Westborough, Massachusetts, layman—along with his extended family—promoted the most radical innovations of the Whitefieldian revivals in New England. After passing through a wrenching conversion experience during the fall of 1742, Stephen starting railing against what he believed were the unedifying sermons of Congregational minister Ebenezer Parkman. His nephew, Isaiah Pratt, experienced visions of the Book of Life; his father welcomed the controversial itinerant preacher James Davenport into his home; his wife and sister-in-law exhorted among mixed audiences of men and women outside the Westborough meetinghouse; and other family members began attending religious meetings in the neighboring town of Grafton. Then, during the spring of 1743, the Fays appealed to Elisha Paine, arguably the most incendiary lay preacher of the era, to visit Westborough.

Parkman was an energetic supporter the revivals and an unusually tolerant clergyman. For months he had labored quietly to resolve his differences with the Fays. But he wasn’t about to take this latest threat to his ministerial authority lying down. In the two stern letters presented below, Parkman warned Paine to stay away from his parish and exhorted John Fay, Stephen’s father and a deacon in the Westborough church, not be “led astray” by the interloping itinerant. Indeed, Parkman’s missives are especially valuable for the powerful equestrian metaphors that anchor his arguments. Like many of his colleagues, the Westborough minister envisioned the Congregational gospel land of light as a series of bounded ecclesiastical enclosures. Itinerant preachers such as Paine threatened to break down these spatial boundaries by enticing lay men and women to “jump over the Sacred Fence” and “Leap over Christs Wall wherewith he has encompassed this holy Enclosure.” Hankering after “other pastures,” the free ranging Fays heralded the emergence of a new breed of religious seekers who would come to dominate the American religious scene by the turn of the nineteenth century.

As I argue in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, the Fays “refused to be bridled” (376). Several family members departed Westborough and migrated first to Hardwick, Massachusetts, and later to Bennington, Vermont, where they helped to organize Separate, or Strict Congregational churches. Stephen, who emerged as the proprietor of the famed Catamount Tavern, eventually abandoned the Congregational establishment altogether.

Written on both sides of a small sheet of paper, draft copies of Ebenezer Parkman's 1743 letters to Elisha Paine and John Fay may be found among the Parkman Family

Papers, 1707–1879, box 3, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. The illustrations below appear by permission. For the complete story of Stephen Fay’s fascinating journey from Congregational insider to spiritual seeker, see Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, 374–379, 386, 394–395, 403–404. On the career of Elisha Paine, see C. C. Goen, Revivalism and Separatism in New England, 1740–1800: Strict Congregationalists and Separate Baptists in the Great Awakening, second ed. (Middletown, Conn., 1987), 115–123. For two excellent discussions of the challenges posed by itinerant preaching, see Timothy D. Hall, Contested Boundaries: Itinerancy and the Reshaping of the Colonial American Religious World (Durham, N.C., 1994); and T. H. Breen and Timothy Hall, “Structuring the Provincial Imagination: The Rhetoric and Experience of Social Change in Eighteenth-Century New England,” American Historical Review 103 (1998): 1411–1439. Genealogical information on Stephen Fay and related family documents may be found by searching the online collections at the Bennington Museum.

Westboro May 19, 1743.

Mr. Pain,

Sir,

I am none of those who lord it over Gods Heritage (as I humbly hope) but have been Gentle and obliging towards my Brethren and therefore have been ready to Countenance & encourage preaching in all their Houses as often as they have desird it both by myself and Others whensoever it could be Agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ or advance & promote his Cause; but have entreated that they would duely observe that necessary Rule & Order which the Great Lord & Head of the Church has requird all his to Submitt to, for their Edification as well as Preservation; But my Brother Stephen Fay has So far broke over these as to apply to you without Saying anything to [me] of it tho he knows I would heartily encourage & promote whatever might tend by the Blessing of God to the reviving and Carrying on His Glory work & Kingdom in this Place, to come into this Place & preach at His House tomorrow notwithstanding that you are such a Stranger to me as that I know not that ever I saw you & therefore cannot know what you are nor what you may be about to deliver to his Dear Flock of the Lord which I have (tho’ most unworthy) the Care & Charge of. I doubt not but that if you are truely one of Christs you will Consider the present State of this Case, & I have many more Things to offer which if known to you would utterly prevent your coming to preach in Westboro at this Juncture. I pray you in the Gentleness of Christ, and beseech you as you Love the Interest of his Kingdom, Suspend at the least your preaching here just now. Begging of God to give a Blessing to this, & Succeed it, I rest your Brother in Christ Jesus

Ebenzer Parkman

Image courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

To Deacon Fay

Dear Brother Fay,

I am grievd to See you under Such Infirmitys, and especially that you do not come to me to take Counsel before you rush on upon So great Things as you are doing. Has not the Great Lord and Head of the Church instituted the Ministry and Authority with which I am vested, and have you not bound yourself voluntarily in an holy Covenant with me, to own and submitt to my Teaching and Instruction & to my watch and Government while I teach and Guide agreeable to the will of the Lord Jesus Christ? Compare Ezekiel 33:7 with Chronicles 3:8, 1 Samuel 4:13 middle Clause, Romans 11:13 last Clause, Hebrews 13:17, 1 Timothy 4:11, Titus 2:15, 2 Corinthians 10:7 to 14, John 10:1, 2; Jeremiah 2:25, Canticles 2:15, 1 John 4:7. Am I, Dear Brother, Lording it over you; or have I not rather abounded in Love & Gentleness towards you? But have I been so unfaithfull to our great & glorious Lord & to you and your Souls Interest as to cause you to forsake me and go away from my Pastoral and Affectionate Care over you? If So why have you not been so faithfull to me at least as to lay before me Conviction of it? Galatians 5:22, Ephesians 4:3, Canticles 1:7, 8. Out of tender Pitty I have Sent these Lines to you, that you may not be led astray. Do not run out of the Fold of Jesus Christ; This is his Pasture; you may be sure of it; don’t hanker so after other pastures as to take off your Heart from this; tho it be mean compard with other[s] yet if we are willing to be where Jesus has allotted us, he will give his Blessing; we shall not want. Psalm 23:1. Don’t be so impatient as to jump over the Sacred Fence, but wait upon him in his own way; And pray let me beseech you for your own sake & for mine and the Sake of the souls about you, but most of all for our Dear & Blessed Lords Sake & his precious Cause & Interest, dont be instrumental to help any Stranger either to break down or Leap over Christs Wall wherewith he has encompassed this holy Enclosure: Nay if there be ever so Seemingly the signs of an Eminent Servant of Christ, yet you may not venture to let him in as a Teacher, & preacher among us but by that Door of which I am tho most unworthy the Guardian. Brother Fay, Christ has Set me upon these walls to look out. If you are asleep, wake up.

Image courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

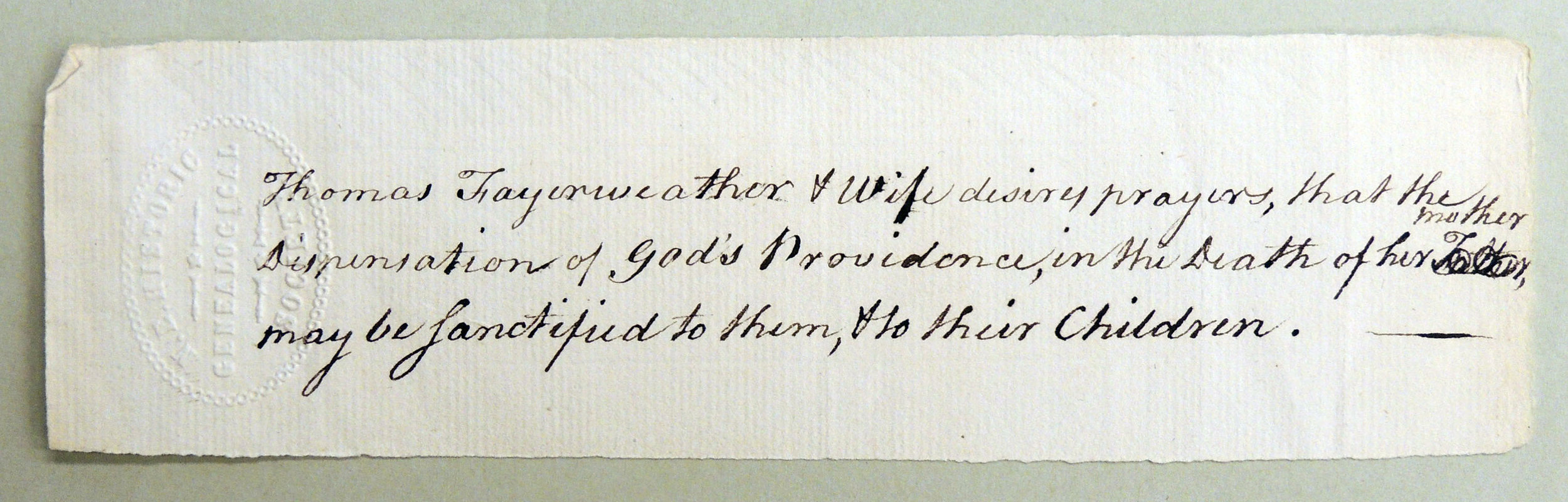

Fayerweather Family Prayer Bills (Boston, 1770s)

I discovered this interesting group eighteenth-century religious manuscripts shortly after Darkness Falls on the Land of Light went to press. They are excellent examples of what New England Congregationalists called prayer bills or prayer notes—small slips of paper bearing prayers to be read by ministers during Sabbath worship exercises. Unlike the few surviving prayer bills, nearly all of which are scattered among the papers of prominent clergymen such as Cotton Mather or Jonathan Edwards, this collection remained in the family of the prosperous Boston and Cambridge merchant, Thomas Fayerweather, and were passed down to his posterity along with his voluminous business correspondence and account books.

As with most prayer bills, the Fayerweather notes fall into one of two major classes. The Boston merchant composed petitionary prayers beseeching God for protection and healing in the face of impending life crises, such as his wife’s pregnancies or the illnesses of family members. During the ensuing weeks, Fayerweather penned prayers of thanksgiving or sanctification in which he sought to demonstrate his family’s resignation to the will of God. The form of each prayer request, moreover, closely followed the standard conventions of the genre, which remained relatively unchanged from the late seventeenth century through the early 1800s. That Fayerweather preserved these ephemeral manuscripts suggests that he may have envisioned the notes as a record of God’s dealings with his family in much the same way that puritan diarists often used their devotional journals to mark remarkable or providential events in their lives.

Baptized as an infant in Boston’s Old South Church, Thomas Fayerweather (1724–1805) was raised in one of New England's wealthiest families. At a young age, he learned the merchant’s trade from his father and spent several years with relatives in Philadelphia and Maryland. Returning to Boston, Thomas married Sarah Hubbard (1730–1804), daughter of the treasurer of Harvard College, in 1754; they had four children between 1757 and 1769. Over time, Fayerweather expanded his business enterprises, trading a wide range of foodstuffs, commodities, and enslaved Africans from Maritime Canada to the West Indies, New York to London, and in ports in Central America, Africa, and Eastern Europe. It is not clear whether Thomas or Sarah ever affiliated with the Old South Church, although they presented their children for baptism in a regular order at the venerable Boston meetinghouse. (His older brother Samuel, by contrast, joined in full communion at the peak of the Whitefieldian revivals in 1741, after he experienced a wrenching conversion and was beset by dramatic visions of Satan.) In later years, Fayerweather moved his family to an impressive mansion on “Tory Row” in Cambridge, Massachusetts. As with many of the “Genteel Folks” of the Revolutionary era, as the future president John Adams described Fayerweather’s elite social circle, he purchased pews in both the local Congregational meetinghouse and the Episcopal church. At the time of his death in 1805, Fayerweather’s estate was valued at more than 64,000 dollars.

The seven prayer bill manuscripts presented below are part of the Thomas Fayerweather Papers, 1737–1818 (Mss 80) at the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston and are reproduced here by permission. I have organized them in chronological order based on the birth and baptismal dates of Fayerweather’s children and the deaths of Sarah Fayerweather’s sister, Thankful, wife of Boston physician Thomas Leonard (d. December 2, 1772), her father, Thomas Hubbard (d. July 14, 1773), and her mother, Mary Jackson Hubbard (d. February 15, 1774). Written on the back of a list financial transactions with business contacts in central Massachusetts, the sixth document includes copies of prayer requests that Fayerweather submitted to the ministers of the Old South Church.

I discuss prayer bills at greater length in “The Newbury Prayer Bill Hoax: Devotion & Deception in New England’s Era of Great Awakenings.” Massachusetts Historical Review 14 (2012): 53–86; and Darkness Falls on the Land of Light, 67–69 (see also 204–205, 452–454, and 563–565 for the spiritual odyssey of Fayerweather’s radical New Light brother). For edited transcriptions of the largest surviving collection of eighteenth-century prayer notes, see Stephen J. Stein, “‘For Their Spiritual Good’: The Northampton, Massachusetts, Prayer Bids of the 1730s and 1740s,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 37 (1980): 261–285. On the broader religious culture of Boston’s eighteenth-century merchant community, see Mark Valeri, Heavenly Merchandize: How Religion Shaped Commerce in Puritan America (Princeton, N.J., 2010). For genealogical information on the Fayerweather family, see John B. Carney, “In Search of Fayerweather: The Fayerweather Family of Boston,” New England Historic Genealogical Register 145 (1991): 57–66; and Harlan Page Hubbard, One Thousand Years of Hubbard History, 866–1895 (New York, 1895), 92–94. A number of Fayerweather family artifacts, including the portraits by Robert Feke displayed below, may be viewed in the online collections of Historic New England.

[ca. 1757–1769]

Thomas Fayerweather & Wife returns thanks to God for his great goodness in granting her a safe deliverance in Child birth & ask’g your prayers that begun Mercy may be perfected,

for perfecting mercy,

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. 1757–1769]

Thomas Fayerweather & wife returns thanks to God for his great goodness in raising her from the perils of child birth & giving her an opportunity to wait on him in his house Again.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. December 1772]

Thomas Fayerweather & wife desires prayers, that the dispensation of Gods Providence, in the Death of her Only Sister, may be sanctified to them.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. 1773]

Thomas Fayerweather & Wife, desires prayers for her Father, very week & low, that God would be pleas’d to Bless the means, us’d for his Recovery, or fit & prepair him, & all concern’d, for his Will & pleasure.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. July 1773]

Thomas Fayerweather & Wife desires prayers that the Dispensation of Gods Providence in the Death of her Father may be sanctified to them & to their Children.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. 1774]

First note.

Thomas Fayerweather & Wife desires your prayers for her Mother; very week & low that God would be pleased to Bless the means us’d for her Recovery or fit & prepair her & all concerned for his Will & pleasure.

2d. note second Sabbath morning

Mary Hubbard with her Children desires the continuance of your prayers for her; remaining very week & low, that God would be pleased to support & prepare her, & all concerned for his holy will & pleasure

2 Note if T Fayerweather & Wife had have put up one was as follows, (not sent)

Thomas Fayerweather & wife desires the continuance of your prayers for her Mother Apprehended drawing near her great change that God would be pleased to fit & prepair her & all concern’d for his Soveraign Will.

NB. The note wrote by Madm. G. as follows not sent.

Mary Hubbard remaining very week and low desires Continuance of your Prayers for her, that God would support her and prepare for his Holy Will and pleasure.

(pray’d to God to support them, & comfort them in their afflictions.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[ca. February 1774]

Thomas Fayerweather & Wife desires prayers, that the Dispensation of God’s Providence, in the Death of her mother may be sanctified to them, & to their Children.

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society.